Christopher Lane

Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities

Northwestern University

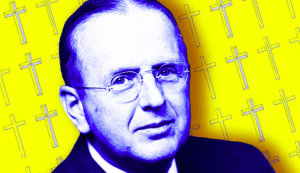

“Trust God, have faith, stick it out.” In the depths of the Great Depression, following years of financial worry and instability, these words by Norman Vincent Peale were a balm to millions of Americans. They offered hope and encouragement, paired belief in oneself with a sunnier future for all, and urged Americans to find religious solutions to individual and national problems.

From his pulpit in midtown Manhattan, with the aid of a vast publishing empire and media platform, Peale issued weekly reminders that well-being and piety were—or should be—inseparable. Belief in oneself was unlikely to endure, he warned, without fervent belief in God. Americans were newly encouraged to see themselves as living “under God,” just as Go to Church messages cropped up everywhere.

Peale’s success lay in binding the nation’s post-War boom to a heightened religiosity he had helped to orchestrate and was ardent in stoking. His most notorious acolyte, Donald Trump, stakes his appeal to voters on similar promises and assurances.

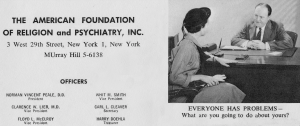

With a group of conservative allies in the early 1950s (among them President Dwight Eisenhower and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, a trove of papers and letters confirms), Peale imbued such promises with stronger religious nationalism than ever before. The American Foundation of Religion and Psychiatry, Inc., the nationwide evangelical organization he cofounded in this same era, encouraged individuals, politicians, and corporations alike “to accept religiously motivated ideas and ideals as a means of solving problems.” Peale himself was clear about the consequences of pairing positive psychology with conservative populism and nationalism: “Emotion breeds enthusiasm, and enthusiasm is that which is necessary to Christian world conquest.”

Christ or Marx?

A surge in public religiosity, it was widely claimed at the time, would rejuvenate the nation and herald its return to preeminence. A mass “return to God” would also, Peale repeatedly asserted, strengthen the population by “inoculating” it against communism—which, because of communism in the USSR (Stalinism in particular), had been cited since the mid-1930s as a grave and worsening threat to the nation’s core beliefs.

For Peale, the question “Christ or Marx?” summed up a then “perilous” national dilemma. With “millions espousing [Marx’s] ideals with fanatical zeal,” he warned in October 1948, in a political sermon he titled “Democracy Is the Child of Religion,” freedom itself was threatened. Religious belief was, by contrast, “the best way to preserve” freedom and was, accordingly, the very principle on which America needed to “crusade.” The evangelical thrust was, for Peale, a consequence of standing united in steadfast opposition to forces such as collectivism. “Thus you have the issue,” he summed up: “Christ or Communism, Christ or chaos, Christ or catastrophe, Christ or the police state.”

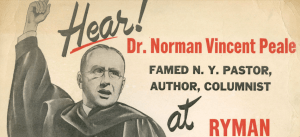

As minister of one of the oldest churches in New York City, Peale was exceptionally well placed to air and promote such claims, to make being unreligious appear unbalanced, fanatical, and wholly “un-American.” He took on the task with relish, using his pulpit to lob almost weekly tirades at Washington.

With the national press riveted by his every move—much as his counterpart today looks to generate comparable media attention—Peale became a lightning rod for national conservative concerns, from the sale of liquor to the perceived threat of labor unions, the godless, and the “alien, un-American ideologies” that, in his view, were behind the threat.

A Gospel of Self-Assurance in an Age of Mass Anxiety

For those who know Peale from his most popular books, such as The Power of Positive Thinking, it can be disconcerting to realize how thoroughly politics imbued his early sermons, talks, and religious activities. Especially in the late 1930s and early 1940s, when Peale was burnishing his reputation as a minister and speaker not just in New York but nationwide, his crammed press folders report the activities and accusations of a man with an extraordinary appetite for political conflict.

During the Depression, Peale was especially active in hardline lobbying groups whose self-appointed mission was to question the New Deal’s very existence, to undermine it even by smearing its White House advocate, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The president, notably, was targeted despite his own allusions to religious belief. Roosevelt’s first inaugural address was so “laden with references to Scripture” that it prompted the National Bible Press to release a chart highlighting the “Corresponding Biblical Quotations”; in his second inaugural address, in January 1937, Roosevelt also likened himself to “a modern-day Moses leading his people out of the wilderness.”

Peale was unpersuaded. One newspaper article, after declaring, “New Deal Assailed as Curb on Reform: Dr. Peale Charges Hasty Moves for Selfish Ends Impede Real Social Progress,” captures the flavor of his blunt attack: “Ill-Conceived Experimentation Makes Public Wary of Progress.”

In the New York Sun, Peale’s target shifted once again: “Peale Assails Class Conflict: Criticizes Methods Used by Roosevelt.” In this piece the New Deal was held virtually responsible for the mass inequality Congress had in fact passed it to redress. The message was unmistakable, and the New York American spelled it out: “Dr. Peale Asks America to Put Roosevelt Out. Country Must Change Him or Change Constitution, He Declares in Sermon.”

It was in alluding repeatedly to the President’s irregular church attendance that Peale found the political vulnerability that suited him as a minister. “Criticizes Roosevelt’s ‘Indifference to Religion,’” the Herald Tribune noted. “Dr. Peale Calls It Cause of Vital New Deal Errors.” Peale was particularly aggrieved by the president’s “Sabbath excursions and fishing trips,” though the relationship of these jaunts to seeming mistakes in the New Deal is still far from clear. President Roosevelt was, Peale said of a conflict over Supreme Court appointees, “a presumptuous seeker after improper power.” In yet another political sermon, he warned ominously of the government’s growing tendency to “autocracy” and the president’s tendency toward “dictatorship”: “We can pull him down when we wish.”

“We Can Pull Him Down When We Wish”

Anticommunism was to Peale and his allies a pro-Christian stance, even if the religious component was not strictly necessary for the critique to hold. Aware of Freud’s insights into the nature of religious enthusiasm (itself of vital importance to the experimental Religio-Psychiatric Clinic Peale had set up with his collaborator, the Christian psychiatrist Smiley Blanton, and to their later national organization, the American Foundation of Psychiatry and Religion, Inc.), Peale knew that fervor could fire up Americans beyond the pulpit, especially when packaged as a promise of national renewal through personal and religious redemption.

“It is increasingly evident,” he was quoted in the Herald Tribune as asserting, “that the only solution to the present [national and international] crisis is a deeper, more spiritual, more social Christianity.” Even more, he urged—in the kind of accusatory turn that made him popular among hardliners adopting the same refrain a decade later during the McCarthy hearings on un-American activities—“the man who shows no interest in Christianity and fails to support it is the real enemy of our social institutions.”

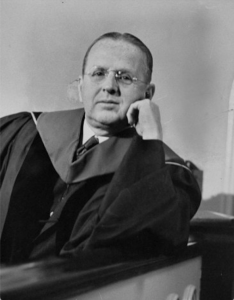

Although far from original, and rapidly adopted by other conservative revivalists, such as Billy Graham, Peale’s claims that faith in God, country, and self were broadly identical acquired importance by dint of their enormous influence and popularity in postwar America. By 1955, The Power of Positive Thinking had sold almost a million copies and was outselling all other books except the Bible. As his biographer Carol V. R. George concluded, “It was Peale’s message that gave definition to the religious revival” of the early 1950s.

Association with Far-Right Organizations

Peale’s association with such far-right organizations as the Committee for Constitutional Government, Spiritual Mobilization, the Christian Freedom Foundation—and, briefly, H. L. Hunt’s Facts Forum—sometimes generated enough controversy to be acutely embarrassing to him.

When a book on hardline conservatives appeared in 1943, noting accurately that Peale had shared a platform with Elizabeth Dilling and the Reverend Edward Lodge Curran, the damage to his reputation was considerable. Dilling, “a person the federal government ranked among the worst hate-mongers” was, notes George, “a ‘patriot’ who smeared liberals, Jews, African Americans, and other ethnic groups with the same broad brush.” Curran, founder of the National Committee for the Preservation of Americanism, was the author of alarmist books such as Spain in Arms: With Notes on Communism and Facts about Communism.

The Power of Religious Nationalism

After throwing his considerable weight behind Senator Joseph McCarthy on the need to expose “subversives” in the federal government, Peale broadcast his upbeat message in The Power of Positive Thinking. The runaway bestseller opened by urging the reader, “Believe in Yourself! Have faith in your abilities!” But Peale quickly pivoted to insisting, as he does in all his other writing, that the faith be religious in character. To maintain it, readers could try “prayer power,” which would aid the nation’s “spiritual mobilization.” The minister was part of a nationalist movement promising “freedom under God” and encouraging Americans to think of their elected representatives as providing nothing less than “government under God.”

By turns pep talk, sermon, and sales pitch, Peale’s book on positive thinking made reference to God ninety-one times, with forty-nine further allusions to the Bible. Originally titled The Power of Faith—and retitled, according to Peale, after some personal reluctance—the book devoted a large portion of its pages to evangelizing. Over and over, its author stressed, religious belief was a necessary condition for belief in oneself and the nation.

By repeatedly equating commercial acumen with piety, uncertainty with religious doubt, and personal and cultural failure with collectivism and godlessness, Peale and his admirers helped redefine religious Americans as socially superior winners (the “better people,” he once called them). By 1957, anything resembling “a low opinion of yourself” had come to seem anathema, “an affront to God” and, presumably, to self and country. Spotlighting the normally hidden underside to positive psychology, Peale warned the nation, “Never entertain a failure thought.” He would tell those prone to such thinking, “[Y]ou’re disintegrating. You’re deteriorating. You’re dying on the vine.”

Peale and Trump

After decades of attending Peale’s services, Trump named Peale and his writings among his strongest influences. Marble Collegiate Church has since disowned the former president, largely because of the excesses and untruths characterizing his 2016 campaign, but Peale’s influence persists in Trump’s careful tying of optimism and renewal with Christian nationalism.

One consequence of this Peale-like association is continued expansion of the equating of health and wealth with religious salvation. Another, directly related, is that failure and disappointment result from inadequate faith in oneself, God, and the nation. Just as Peale did in the 1950s, Trump declared in January 2016: “Christianity, it’s under siege.” Then, and since, the former president pledged to “protect” the religion as president. According to 2016 election data, white evangelicals voted for Trump by an 81-16 percent margin, mainline Protestants by 58-39.

White Evangelicals and Trump

Peale half-counseled, half-preached that religious faith was essential for the achievement of wealth and success. Trump’s broader or vaguer message is that national success and affluence appear “blessed,” religion (and, specifically, Christian nationalism) being the path to personal and national redemption. The unbelieving and the differently religious may wonder if they have any real presence in this vision of America. In his Union League speech in Philadelphia, Trump made a statement bearing equal parts promise and threat: “We will be one nation, under one God, saluting one flag.”

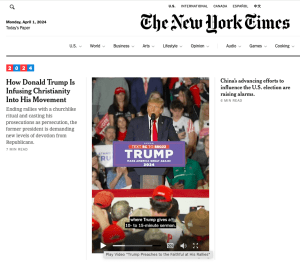

Once again on the campaign trail, this time facing 88 felony charges and four criminal trials, the now twice-impeached former president is again turning to religious nationalism and Peale’s efforts at binding belief in self with belief in God. According to yesterday’s New York Times, the former president has taken to “demanding new levels of devotion” from his followers by “infusing Christianity into his movement.” The final minutes of his political rallies are now given over to an “almost solemn, churchlike atmosphere,” in which the former president “gives a 10- to 15-minute sermon.”

The edition of the Bible that Trump began selling over Holy Week (during which he also compared himself to Jesus) is embossed with an American flag and the words “Holy Bible — God Bless the USA,” a pristine example of religious nationalism and an almost literal enactment of Sinclair Lewis’s famous warning, “When fascism comes to America, it will be wrapped in the flag and carrying a cross.”

[Adapted and updated from “The True Mission of Donald Trump’s Pastor,” The Daily Beast, Jan. 15, 2017, from Surge of Piety: Norman Vincent Peale and the Remaking of American Religious Life, Yale University Press, Nov. 2016.]

Among the topics the book illuminates:

— How anticommunism in the 1930s and 1940s was turned into a pro-Christian, pro-American stance.

— Why evangelical Americans today so often return to the cultural and political concerns that roiled the 1950s.

— How secularism was made to seem at odds with normalcy, with neutrality toward religion cast as a sign of weakness.

— How Freud’s ideas played an unintended role in promoting America’s religious revival.

— How organizations founded by Peale served as a bridge between the nation’s religious communities, its psychiatrists and psychologists, and its business and political leaders, bringing them all into closer alignment.

“In Surge of Piety, Christopher Lane ably shows the ways in which Norman Vincent Peale’s potent combination of Protestant Christianity, popular psychiatry and nationalist politics helped remake America.”—Kevin M. Kruse, author of One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America

“… reveals a surprisingly understudied dimension of Eisenhower’s political consensus: the religio-psychiatry of Norman Vincent Peale. Lane’s is a fascinating and accessible reassessment of a pivotal political moment, and the enduring fusion of popular religion and psychology in American life.”—Darren Dochuk, University of Notre Dame

“Enthralling … graceful and well-paced … requisite reading”—Mitch Horowitz, Washington Post

“… tells the story of Peale’s rise and fall crisply and without malice, even when Peale is at his more-huckster-than-minister gauchest”—Ray Olson, Booklist